Entanglements of the Asian Identity: Visibility and Representation in the United States

- May 1, 2022

- 22 min read

Updated: Jul 21, 2025

This piece was originally posted on the USC Digital Library

“Sorry man, I only got pork sausages … ran out of everything else.”

The hot dog vendor was kind and professional, but certainly not on target when it came to recognizing his client. As someone with a Hindu name from a predominantly Hindu country, the fair assumption about me would’ve been that I don’t eat beef … though that would still been incorrect because I’m not religious. Yet, it wasn’t the first time someone looked at me and thought I’m Muslim. My name, Karan, also sounds like “Quran” if you say it with an American accent, which further adds to the layman’s perception of me.

As a third-culture kid who has repeatedly switched between living in India and the United States from an early age, I developed a heightened sensitivity to the different shades of the Asian identity. I am ethnically Indian but American on paper, so the way people communicate race, culture and nationality across the Pacific Ocean has always fascinated me. Here, individuals are habitually identified by complexion or eyes or lips or hair, but rarely their experiences.

In my freshman year of college, which was also my first extended stay in the United States as an adult, I noticed a lazy identification pattern that immediately stood out to me. During a class discussion, a student from Assam (a state in northeast India) and I were identified as “Asian” and “Indian” respectively. People from Assam, because of their geographic location, have some similarities in appearance with East and Southeast Asians that, with distance, blurs their identities into one. This confused me because I’m also Asian while the other student was also Indian. Over the years, as people have referred to me as Arab, Middle Eastern and Muslim (usually because of my physical traits) without showing any interest in my actual identity, I realized that the brittle rationale behind clumping cultures together runs rampant in American dialogue.

A PEEK IN THE REARVIEW MIRROR

Cultural erasure was built into the social structure of the United States since the very beginning, and the American public, notwithstanding its immense diversity, actively participates in it. My interactions have taught me that the complexities of Asia have been obscured by an indifference to the country’s rapidly evolving racial and cultural dynamic.

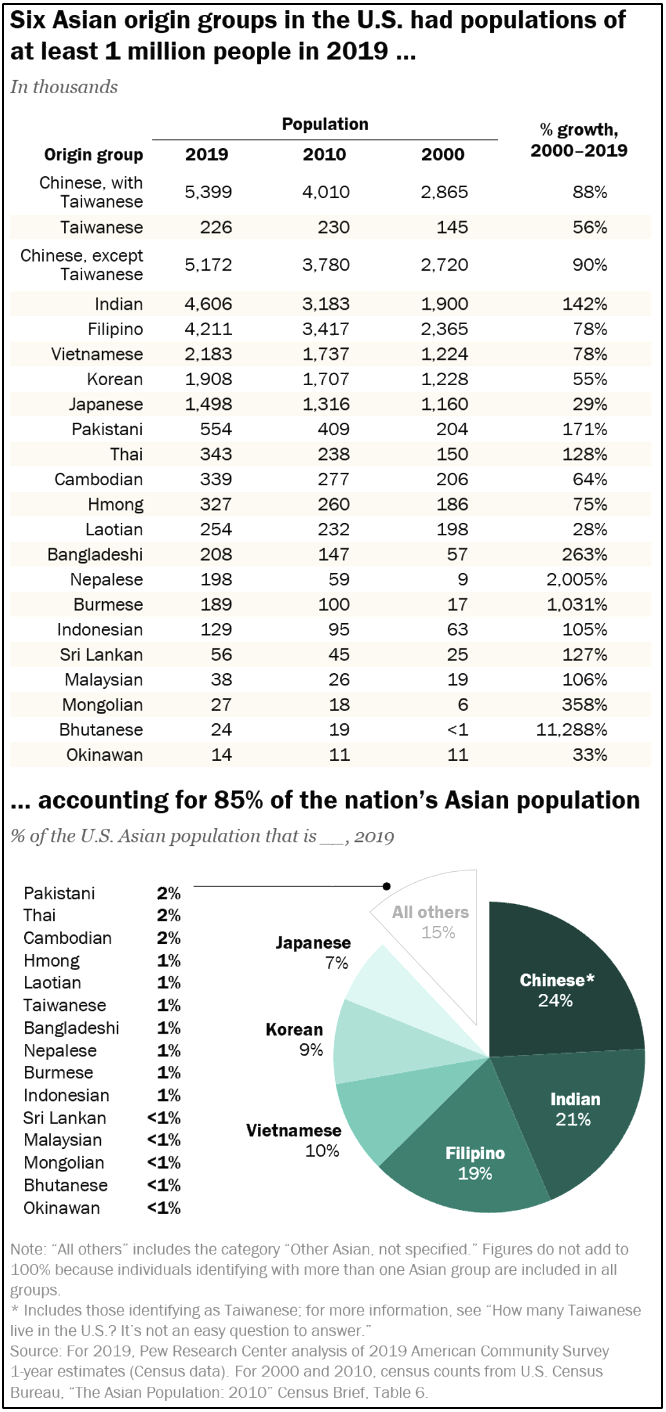

Historically, East and Southeast Asians were among the first to immigrate to the United States in large numbers and establish their own communities. Their shared struggles of being ousted in a Eurocentric space resulted in the convergence of the pan-Asian identity. From the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 to the Japanese American internment camps commissioned after World War II, a glaring track record of being “othered” resulted in these communities forming a contingent of their own. In the 21st century, Asian Americans consist of over 50 ethnic groups and have become the country's fastest-growing racial or ethnic group. The United States is now home to people who originate from Central, East, South, Southeast and Western Asia — the general area that was mashed into an all-encompassing unit and dubbed the “Orient” by Western imperialists.

The word “Oriental” was originally wielded by European colonizers to accentuate the alien exoticism of the East in a way that conflated handicrafts, ornaments and lifestyle, i.e., objects and people were displayed and treated with the same fascination. As immigration from other parts of Asia began to proliferate, the term came to be used mostly in reference to East and sometimes Southeast Asians, most likely because they have a denser presence in the country. In recent years, the dehumanizing origins of the word have been widely denounced, birthing a socially acceptable euphemism: “Asian.”

The Associated Press Stylebook: the central standard of communication for American journalists

NEGOTIATING AN UGLY PAST

Though the general consensus among the people “Oriental” most recently referred to is that it’s a humiliating term, some still see the value in reclaiming it to amend a Western-dominated narrative.

Jane Tsuchiyama is a 64-year-old Japanese American who closely identifies with the Oriental tag. She is a well-reputed acupuncturist based in Hawaii, though her success today belies a childhood bruised by hardship. Both her parents were sent to internment camps following World War II, after which they shuffled around parts of the Midwest before settling in Chicago. She had a lower-middle-class, blue-collar upbringing in Garfield Park, a racially divided neighborhood in the city where her family always felt out of place. For that reason, Tsuchiyama’s parents raised her and her brother to be “as White as possible.”

Still, they were bullied at school and called names. She remembers being sexualized since the age of five, having kids hurl stereotypes that are, to this day, attributed to women with her features. Her older brother had it even worse — he was beaten up on several occasions and repeatedly had his belongings stolen or raided by other students because he was labeled an introverted “geek.” Their father also passively tolerated the same treatment on a regular basis, with people insulting his looks and heckling him at stop lights on multiple occasions. Tsuchiyama recalls how he “would quietly drive on,” desensitized to the mockery that had become a fixture in their lives.

She kept her anxieties to herself in the hope of not causing her parents any stress, but it was difficult for her to deal with emotional trauma at such a young age. Yet, it was that environment she wanted to get away from, not her race.

With time, Tsuchiyama was able to gain strength and embrace her cultural roots. She went on to make a career out of a practice that has deep ties to East Asian culture. Her interpretation of acupuncture borrows elements from the different regions that have mastered it, from China to Japan to Vietnam, and more. Her craft evolved under the “Oriental” banner like other businesses and practices in the United States throughout the 1990s, such as the Oriental Trading Company and the Bank of the Orient, which is why the term has never bothered her. Similar to how the United Negro College Fund (UNCF) and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) have retained archaic terms in their names while continuing to help marginalized communities, Tsuchiyama believes there’s a history attached to “Oriental medicine” that needs to be recontextualized. Hence, when New York Rep. Grace Meng sponsored a legislation to remove the term “Oriental” from federal law in 2016, Tsuchiyama became a strong advocate of the word.

That same year, she published an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times titled, “The term ‘Oriental’ is outdated, but is it racist?” In the article, she acknowledges that the word in question is old-fashioned and that it was originally used when “exoticizing stereotypes was prevalent,” but also states that it refers to the East just as the Occident refers to the West, and that “geographic origin is not a slur.” Given that her execution of acupuncture fuses the different cultural practices from a general region, it’s no surprise that she doesn’t find broad categories offensive. Tsuchiyama asserts that she has been called derogatory slurs since her childhood, from “Chink” to “slant eye” to “zipperhead,” but that “Oriental” is not one of them; contrarily, it’s a term she takes pride in because it symbolizes her skill and its tradition.

She is on the board of the National Certification Commission for Acupuncture in Oriental Medicine, and they have developed medicines that help combat opioid addiction and back pain. More importantly, they are drafting a bill for Congress to include acupuncture as part of Medicare. Amid these strides, the pressure to drop the word “Oriental” deeply upsets her. Since the practice is certified under “Oriental medicine” in over 45 states, changing it would require legislation across the country. This would considerably delay the work her community of specialists is trying to do to help those in need. “It’s a conundrum of what we call ourselves rather than what we are doing,” she said. “A mission without significantly positive outcomes.”

Tsuchiyama is nearly 40 years older than me, so there is an apparent discrepancy in how much importance we give words. Whereas I can make sense of her sentiments and the rationale behind them, they are specific to her vocation and the inconveniences it currently faces, not the larger Asian American community as it exists today. Younger generations are more intolerant of microaggressions because the country we inherited is not as blatantly hostile as it once was. Preventing the conditions that those before us managed to prevail over is now within reach. Whereas our concerns might seem trivial in comparison to what they endured, language reflects how people are perceived, and therefore, treated.

Though Tsuchiyama’s article is compelling, there are parts of it that haven’t aged well. It was published roughly three and a half years before the coronavirus outbreak that triggered a rise in hate crimes against people with “Asian” features. When Tsuchiyama wrote, “A wave of anti-Oriental discrimination is not sweeping the country,” she overlooked the racial and xenophobic hostility that has bubbled underneath the surface throughout the history of the United States, sporadically culminating in violent outbursts. One example of this is the 1982 killing of a Chinese man named Vincent Chin, who was beaten to death in Detroit by two White automotive workers. Japan’s success in the auto industry had cost several Americans their jobs, especially in Detroit since it was the hub of automotive manufacturing at the time, and the culprits blamed Chin for it. Whereas there is no right target for violence, the fact that a Chinese man was mistaken for Japanese brings attention to a trend of hyper-conflation that remains alive and well to this day. One of the earliest incidents that sparked the “Stop Asian Hate” movement was the murder of Vicha Ratanapakdee, a Thai American man, in early 2021. The coronavirus pandemic put China in the hot seat all over the world. I was in India when this happened, and a large number of people from the northeast region of the country were the victims of hate crimes because they have features that loosely resemble the Chinese.

Aside from the larger issue of racism, generalizations based on physical features, contrary to Tsuchiyama’s perspective, do indeed have dire consequences.

THE GRAVITY OF DIALECT

On the other side of the debate over the power of words is Henry Fuhrmann, a former copy editor who worked at the Los Angeles Times for 25 years. He has also served on the board of the Los Angeles chapter of the Asian American Journalists Association (AAJA) for the last 20 years. His contribution to journalism took shape in ensuring that issues were communicated in a focused and productive fashion. A proponent of polite and good-mannered language, he insists that altering vernacular is “not hard, but made to look hard.” Fuhrmann ran the copy desk at the Times for seven years and also took on the role of standards editor, and this has made him an expert on the “consistent, thoughtful rendering of the actual words.”

Much like myself, he believes that language and identity shape one another, particularly in matters of race, culture and nationality. When it comes to language, prioritizing the ease of communication discourages a thorough understanding of someone’s identity. To this point, vernacular convenience overlooks the intricacies that make us unique individuals.

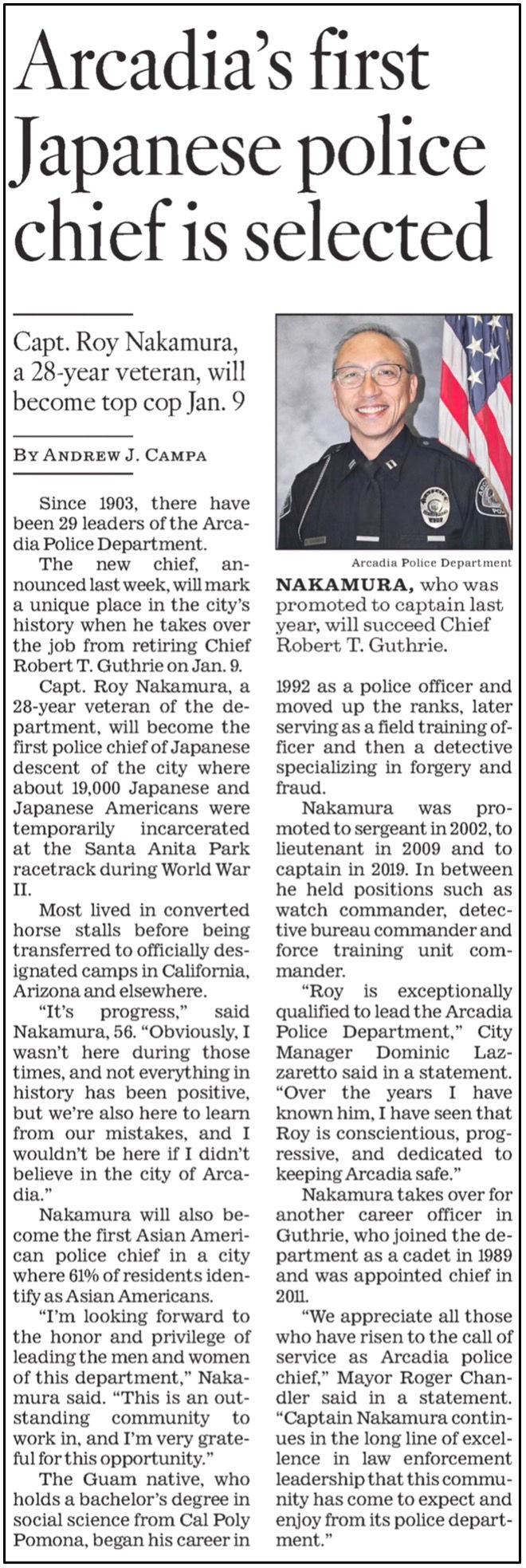

"Labels are blunt instruments — they lack nuance,” Fuhrmann said. “It’s a shorthand to introduce a larger topic of nuance. Sometimes, unfortunately, we stick with the label and don’t get deeper into the details.” His mother was a Japanese immigrant and his father a German American serviceman in the navy. Born in Japan and raised in Southern California, he watched his mother transition from Japanese to Japanese American as she acquired citizenship a decade after moving to the country. Such technicalities are of paramount importance to him. While discussing the shift from print to online, he referenced a Times article from 2020 to illustrate how the latter is free from the constraints of fitting a set number of letters within a box. The digital headline read, “Arcadia, a WWII incarceration site, names its first police chief of Japanese descent,” whereas the newspaper version read, “Arcadia’s first Japanese police chief is selected." The word “American” is key because it's the difference between a citizen and a foreigner. This point was particularly sensitive to the story because the city in which the police chief was appointed was also where thousands of Japanese and Japanese Americans were incarcerated in the aftermath of World War II.

“The solution is often specificity,” Fuhrmann said. “If someone’s identity is germane to communication in your story, your podcast, your TV segment, whatever your form of media is, then identify them the way they want to be identified.”

He has established himself as a voice of authority on such matters. In 2018, he published an essay on Conscious Style Guide titled, “Drop the Hyphen in Asian American,” that gained a lot of traction. Soon after it started making the rounds, the Associated Press Stylebook and BuzzFeed Style Guide updated their respective styles accordingly by 2019. Two years later, the New York Times followed suit. These changes were all prompted by Fuhrmann’s insistence: “those hyphens serve to divide even as they are meant to connect. Their use in racial and ethnic identifiers can connote an otherness, a sense that people of color are somehow not full citizens or fully American: part American, sure, but also something not American.” Most major publications now comply with this guideline.

The Los Angeles Times guidelines (1993) — one of first publications to drop the hyphen

“I prefer to say guidelines instead of rules because I was open to interpretation,” Fuhrmann said. “Guidelines are created by human beings — they evolve over time, and we should be open to exceptions and knowing that language changes, and that our sensibilities change.” In this spirit, he too has adjusted his vocabulary to accommodate the needs of others. Until recently, Fuhrmann proudly identified as “Hapa,” which is a Hawaiian term for people of mixed ethnic ancestry but also commonly used by those who are half Asian. He felt that it perfectly described him given his half Japanese roots but was unaware that its immoderate use was bothersome to many native Hawaiians. This came to his notice only when he read an essay titled, “Hapa: A Unique Case of Cultural Appropriation by Multiracial Asian Americans?” published on the same platform as his hyphen piece. He made the conscious decision to stop using the word because the essay shed light on the hurtful effects of borrowing an identity “without the experience of colonization and inequality” of native Hawaiians. “I miss it, but it’s not painful,” he said about giving up one of his favorite terms of self-identity. “It’s more painful for the people who are offended by it.”

ASIA V “ASIANS”

The complications of the Asian American identity are manifold, and Fuhrmann recognizes that representation even within the community isn’t yet holistic. Because he has worked on language for so long, “Asian” to him literally means people of Asian origin, but he is also aware that its most common usage refers only to a selective portion of the continent. The region has been split into ambiguous categories based on how people are distinguished, each treated differently than the other.

“Asian” most often means people from East Asia due to some intersections in appearance and customs as seen in Crazy Rich Asians, while “Arab,” “Middle Eastern” and “Muslim” make up another large group of Asians, clumped together based on a vague set of attributes like Islam, headscarves, turbans and brown skin.

Findings from a 2019 research project by Jennifer Lee and Karthick Ramakrishnan

A 2019 study put the government’s definition of “Asian” to the test by comparing it to how people from other racial categories use it. The results showed that most White, Black, Latino and Asian Americans are referring to East Asians when they use the term. Indians and Pakistanis, who fall under the legal definition of Asian, aren’t usually identified as that.

My own experiences with being mistaken for Arab, Middle Eastern and Muslim demand a better understanding of what those terms denote. Arab is an ethno-linguistic category for people who speak Arabic as their native language or have ancestors who did. Middle Eastern, on the other hand, is far more fluid in that its meaning changes based on the subject at hand — climate, religion and economics each have different borders but a shared name. Muslim, despite its widespread misuse, has the most straightforward meaning: adherents of Islam.

The failure (or refusal) to understand Asia in its fullness has made mischaracterization a common recurrence in the conversations surrounding it. That is why a Muslim from Bangladesh might be confused for Middle Eastern while an Indonesian, the largest Muslim country in the world (an estimated 229 million this year), might be referred to as “Asian." A shallow interpretation of these cultures has given way to a widely accepted rhetoric that validates ignorance.

THE SPECTRUM OF RACIAL ATTITUDES

Farrah Hassen is a policy analyst and writer who regularly scrutinizes the underrepresented and misunderstood side of Asia that her own identity as a Syrian American is tied to. Additionally, she is an adjunct professor in the political science department at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. She previously served as a political advisor to the Syrian Ambassador to the United States at the Embassy of Syria in Washington, D.C., but resigned a few months after the war broke out since she wanted no part in the ensuing human rights violations in her country of origin. Hassen then moved to Egypt and worked as an election observer following the Egyptian Revolution of 2011. Though she isn’t a full-time journalist, she writes a weekly column in the San Gabriel Valley Examiner and occasionally publishes articles for outlets of the Institute for Policy Studies. She writes from the different viewpoints of her distinct American experience, switching between her Arab, Syrian and Muslim identities based on the subject at hand.

This year marks the 11-year anniversary of the war in Syria. In March, Hassen published an article on Foreign Policy in Focus to reiterate the anguish of an ongoing war as it gets overshadowed by a newer one. A total of 610,000 people have died in Syria since the conflict began, but over time, the American public has grown numb to certain parts of the world being in a continuous state of turmoil. Even though Russia has continued its war in Syria, its invasion of Ukraine has elicited far more sympathy from the media and politicians, and the people they influence. To further elaborate on this, Hassen wrote a piece for OtherWords where she addressed how the American media has covered the war in Ukraine and the public’s reaction to it. She points to CBS News correspondent Charlie D’Agata’s (perhaps the most infamous example, among others) comments: “[Ukraine] isn’t a place, with all due respect, like Iraq or Afghanistan, that has seen conflict raging for decades. You know, this is a relatively civilized, relatively European — I have to choose those words carefully, too — city where you won’t expect that or hope that it’s going to happen.” The fact that his words were so effortlessly condescending even after careful thought speaks volumes. Hassen emphasizes how Syrian refugees have been treated with “suspicion and hostility,” with more than 30 United States governors who have tried to close their borders to asylum-seekers. At the peak of the war in Syria, President Donald Trump barred citizens of seven predominantly Islamic countries from entering the United States, implementing what came to be known as the “Muslim ban.” People from Southwest Asia and the Middle East have been dehumanized and denied compassion while Ukrainians have the world on their side when confronted with an equally destructive crisis. The polarity is striking — within a month of the war breaking out in Ukraine, the president announced that the United States will welcome as many as 100,000 Ukrainian refugees; more recently, he proposed a $33 billion aid package for Ukraine.

Hassen reveals these disparities by comparison: “Western journalists lift up President Biden and other global leaders’ rightful denunciations of Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine. But they often remain silent when these same leaders fail to condemn — or even aid and abet — violations of international law elsewhere. This is evident in the over 50-year Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories, as well as the war in Yemen.” The United States remains one of Israel’s strongest allies, obscuring from the public’s consciousness the atrocities being committed against the Palestinian people — as of mid-April this year, Israeli forces have killed 47 Palestinians, including eight children. This is the byproduct of an anti-Islamic rhetoric centered on congenital terrorism, a whole other breed of discrimination that has become prevalent in 21st century American culture.

In a different article published last year on OtherWords, Hassen discussed this issue of Islamophobia in the United States and the surge in hate crimes against people “perceived to be Muslim” in the two decades following the September 11 attacks. From 2000–2009, anti-Muslim crimes spiked by 500% and its residual effects persist to this day. Today, Rep. Lauren Boebert can casually get away with referring to Rep. Ilhan Omar as a suicide bomber, the "Jihad Squad member from Minnesota" and an "honorary member of Hamas." Republican leaders have remained silent and Boebert has proceeded with her career without any formal repercussions. The normalization of such behavior from the country’s leaders cannot be isolated from the 500-plus incidents of Islamophobia that were documented in 2021; it cannot be separated from Omar receiving hundreds of death threats following Boebert’s mockery.

In the United States, those perceived to be Muslim, Arab or Middle Eastern are often deemed barbaric and uncivilized, and treated like lower-class citizens. These hateful sentiments have very little to do with who people truly are or else adherents of Sikhism wouldn’t have suffered from the collateral damage of Islamophobia.

ERRONEOUS TECHNICALITIES

The way individuals are classified is directly proportional to how well their needs are addressed and fulfilled. The latest U.S. Census determined the allocation of approximately $1.5 trillion annually in federal tax dollars to local communities across the country; this data will be used till the next decennial tally in 2030. The census, however, is crucially imprecise because its sweeping categories restrict fair representation.

The Census Bureau is accommodating of Fuhrmann’s and Tsuchiyama’s race and ethnicity, as well as my own. Among the five categories that are offered, we get to mark the box that says “Asian” since it includes Japan and India. The other options are White, Black or African American (an odd categorization because it does not include people of African origin who aren’t Black), American Indian or Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander — each of these specify the regions they apply to. But nowhere in the listing under “Asian” is there any mention of the countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA); instead, they are listed under “White.” The existence of individuals belonging to said group is thus garbled — they are counted but not seen.

The U.S. Census Bureau’s guidelines for race

An inaccurate identification system has ramifications because the data on race influences policy decisions “particularly for civil rights” and is used to “promote equal employment opportunities and to assess racial disparities in health and environmental risks.” Maya Berry, executive director of the Arab American Institute, said the absence of MENA representation has deprived the community of basic services and rights such as voter protection, language assistance and educational grants. The contorted “White” label also misleads universities and companies that refer to the government’s findings to promote diversity. Moreover, it limits research on key issues such as health trends in different communities. Because the Arab/Middle Eastern/Muslim American perspective is rarely given any consideration in matters regarding public advancement, its fluctuating inclusion in American society is puzzling.

The 2020 U.S. Census form

People who have never been treated as White are forced to contribute to statistics that doesn’t don’t benefit them, in government funding or social acceptance. The United States’ imbalanced response to different conflicts and wars is a testament to this overt bias.

CONVEYING AN UNDER- AND MISREPRESENTED EXPERIENCE

Los Angeles Times television critic Lorraine Ali is no stranger to prejudice. Her father was an immigrant from Iraq and her mother a native Californian of French Canadian ancestry, but it was specifically her last name that negatively affected how others viewed her. From early in her life, she's had a conspicuous presence in spaces she was not expected to be: growing up in a predominantly Jewish neighborhood, starting her career as a music journalist covering the punk scene in 1980s Los Angeles, writing about sociopolitical issues while everyone saw her as a “music critic.” She spent the 2000s working as a senior writer at Newsweek, during which time she began branching out and shedding light on the predicament of Muslims in the United States following the September 11 attacks. Her articles were reaching millions of readers, and this put her on the radar of anti-Muslim media propagandists like Steven Emerson and Breitbart News. Political commentator Daniel Pipes even devoted an entire blog page to why she is “the Worst Political Reporter in America.” An obsessive series of chronological updates on her work, the gist of his entries was that Ali is a dishonest and un-American alarmist who defends Islamic extremism. One of his entries from 2008, concise and to the point, reads as follows: “Lorraine Ali writes in the ironically titled ‘Having Kids Makes You Happy’ about the joys of childlessness. Thank you, Ali, for your insights.” Ali has since raised a son and Pipes’ blog page has been inactive for over a decade.

The audacity of a Muslim American woman with a loud voice in the Western mediasphere doesn’t sit well with a lot of people. When Ali was awarded the National Arab Journalists Association's Excellence in Journalism Award, Newsweek editor-in-chief, Jon Meacham, told her she shouldn’t be proud of it. Other writers and editors told her to be careful of the “hot-button topic” she would often write about because of her last name, which frustrated her, because they had reduced Muslims to a topic whereas she was reporting on them as fellow human beings. And this has been a defining characteristic of her writing: empathy for the defenseless.

Ali suspects she lost her job at Newsweek because she had broadened the scope of her work and become a culture writer who was addressing contentious subjects. She moved back across the country from New York City and got a job at the Los Angeles Times, once again as a music critic before transitioning into her current role. She now has more freedom to write about what she wants — “Pop culture, immigrant culture, my own experience, Muslims, Asians.” Today, her work ranges from writing forthright television reviews to dissecting the status quo to illuminating cultures that remain unseen. She punctuates her writing with personal anecdotes and the conviction with which she presents her observations allows readers to expand their vision.

“The last two decades have arguably been the hardest I’ve experienced as a journalist and the daughter of an immigrant who left the tribalism of his old country behind for the wide-open promise of the West. Few things are worse than having to defend your intentions, your faith and your loyalty to your fellow countrymen. I too was weaned on Scooby-Doo reruns and McDonald’s jingles. Isn’t that enough?” — "20 years after 9/11, an American Muslim recalls the costs of war you didn’t see on TV” by Lorraine Ali

Like Hassen, Ali has also pointed out the flaws in the Western media’s coverage of the Arab, Middle Eastern and Muslim regions. “But by the time the fallout from years of war made its way to Europe, in the form of Arab and North African refugees who poured in by the millions, the press had grown tired of covering the war on terror, much less its reverberations,” she wrote in a recent piece. “Without a personal connection, that human tragedy was just old news, and the refugees were a ‘crisis.’” Another article she published close to the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks looked back on the casualties of the war on terror. She energizes her writing by reflecting on the hardships she faced during the influx of Islamophobia at the time of the incident. By referencing “the hate mail and threats, the trolls and profiling,” she gives readers a first-hand account of the Muslim American condition in a post-9/11 world.

In moving away from the more serious matters and into the domain of television, she keeps an eye out for projects that serve a greater purpose than mere entertainment.

A 2018 study on MENA representation in television revealed that 78% of the time, MENA series regulars are terrorists or tyrannical soldiers, whereas 67% of the time they have inflated accents, furthering the notion that they are foreigners. By bringing attention to shows like Ramy, We Are Lady Parts and Our Boys, Ali has opened the Times’ readership up to a side of the MENA identity that is often eclipsed by derogatory caricatures.

“A lot of people don’t want to be learning while they’re watching television,” she said. “The sign of a good show, to me, is that you’re learning something new, and you don’t even know it.” This is precisely why she sees the value in a show like Never Have I Ever, a coming-of-age comedy about an Indian American family based in San Fernando Valley, California. Ali wrote about how closely she can relate to the story even though her Asian lineage traces back to the Middle East. I myself saw resemblances between the characters on the show and my own family, and since Ali did too, that means Iraqi and Indian culture aren’t completely different either. Asian cultures do indeed have similarities, but it is important to recognize what they are beyond superficial traits like chopsticks and headscarves.

SIMILAR YET SO DIFFERENT

Several first-generation Asian Americans have comparable upbringings, united by strict yet loving parents who, in more ways than one, can be embarrassing to children trying to blend in. This is because a lot of immigrants share an objective in raising their kids away from the cultures they leave behind: a strong-willed commitment to ensure their sons and daughters are positioned to succeed.

Ali’s upbringing was no different. Humiliated, she’d sink into her car seat when her father would drive her to school playing a cassette tape of Quranic sutras on the stereo. Visible cultural differences often make the children of immigrants question where they belong in society. Tsuchiyama also stood out beside her peers but eventually grew indifferent to their ridicule. Both Ali and Tsuchiyama have put up with verbal abuse in different forms over their lives, which is why they both feel that the sentiments behind what people say are the actual problem.

A fixation on words, they think, is counterproductive when there are more important things to worry about. Their concerns, however, differ vastly. Fuhrmann is more sympathetic to Tsuchiyama’s outlook given that his mother worked as a seamstress for the now-defunct Oriental Drapery Co. in Oxnard, California. Still, he is optimistic that younger generations are reinterpreting language for the right reasons, namely inclusivity and accuracy. Along with Ali, Hassen and Tsuchiyama, he too stresses the need for a “universal standard for compassion.”

“An injury to one is an injury to all,” Hassen said. “It’s an affront to justice if it’s an affront to respecting human rights. Regardless of how we identify ourselves, there should be a core set of standards.”

In an article published by Vox last year, a number of scholars offered their thoughts on the term “Asian American” and its larger implications. Many consider it inadequate due to the large surface area it covers and the blurring of cultures it validates. Furthermore, when the label stretched out to include Pacific Islanders, a lot of the communities it then pertained to rejected being categorized that way. After all, Tahiti and Kazakhstan have very little in common. Sela Panapasa, a researcher at the University of Michigan who identifies as a Pacific Islander, believes that the “Asian American and Pacific Islander” tag only worsens the invisibility her community has felt throughout history.

The ideological and economic differences between the communities bundled under this sizeable category remain in the shadows because it has very few stakeholders, most notably East Asians. Still, UC Riverside political science professor Karthick Ramakrishnan believes that a shared history of exclusion laws and immigration bans is a uniting factor regardless of how far-reaching the group might be — “What makes us Asian is a history of exclusion.”

Whereas the Chinese Exclusion Act and the Muslim ban were both products of scapegoating, the similarities between the affected cultures remain tenuous. Only a handful of issues plaguing the larger Asian American cohort have been constructively addressed. This is clear from the outpouring of global support that helped launch the “Stop Asian Hate” movement soon after the rise in hate crimes during the coronavirus pandemic. Islamophobia, on the other hand, had been a pressing concern in the United States for two decades before that, but it never prompted a campaign of its own. Charles Tilly described a social movement as a “sustained challenge to powerholders” through “repeated public displays of that population’s numbers, commitment, unity, and worthiness,” and this is precisely what separates the above issues. The pushback against Islamophobia never garnered public sympathy the way “Asian hate” did, which is why it’s necessary to separate the two despite the technicality that integrates them.

Broad-strokes, in-group/out-group classifications impact how we view other cultures with a limited capacity. The Asian American condition, when taken as a whole, must be observed as a multi-dimensional entity existing in many parts with both similarities and differences, some subtle and others stark. Breaking down its expansive categories to properly acknowledge the assorted elements within—religion, geography, economics, politics, education—paves the way for the fair representation of Asian Americans.

EPILOGUE

“Nah, pork is fine,” I told the hot dog vendor.

This caught him off guard. When I noticed the embarrassment on his face, I smiled and spoke up: “I eat everything.” This sparked a brief conversation between us that let me explain why — just like him, I had no visible dietary restrictions, and just like him, I was more than what I appeared to be.

His intentions were pure and that’s all it took for me to engage with him. I’m not offended by people who don’t know better; contrarily, I consider it my responsibility to help them widen their line of sight.

Effective communication is central to seeing and being seen — I’ve learned this first hand.

Comments